I know genomes. Don't delete your DNA

Too many people are panicking about 23andMe.

As word spread last year that 23andMe was about to go bankrupt, many of their millions of customers wondered if they should delete their data. Social and conventional media were quick to offer advice, sometimes coming from experts in genetics and genomics–my field, I should note–on how to go onto the 23andMe website and delete all of your data.

In March of this year, the California attorney general issued a warning that 23andMe was “in financial distress,” and he told Californians that they ought to seriously consider deleting all their data. The Washington Post was even more direct: “Delete your DNA from 23andMe right now,” they wrote in a headline. Why? Because your privacy is at risk, they claim.

I didn’t delete mine. Now, just a few month later, 23andMe is back from bankruptcy, and the Washington Post once again told everyone “you should still delete your DNA.” I’m still not going to do that. Let me explain why there’s really nothing to worry about.

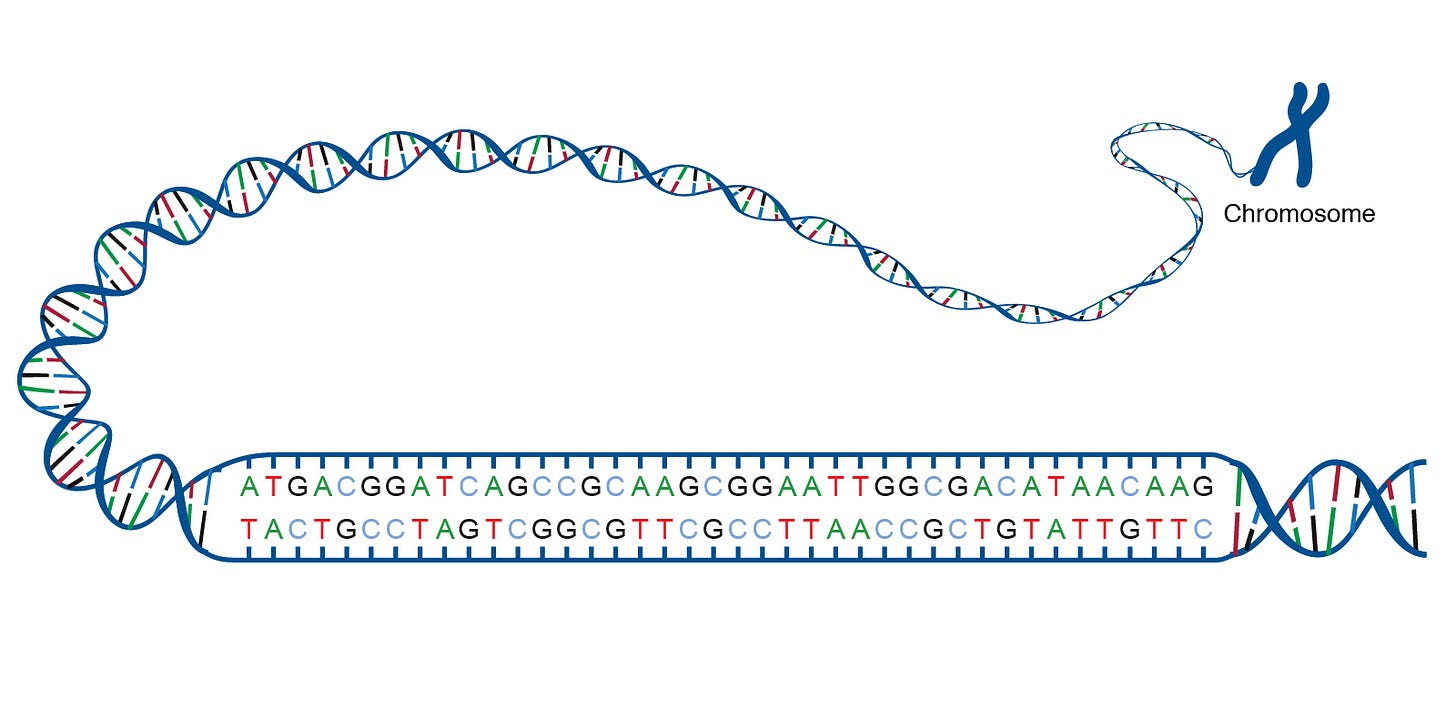

First, what exactly does 23andMe collect from its customers? Despite the near-hysterical warnings from the WashPost and other sources, 23andMe doesn’t have “your DNA.” Your genome (which contains all your DNA) has 23 pairs1 of chromosomes (that’s where the name 23andMe comes from), and all together they add up to about 3.1 billion letters (nucleotides) of DNA. It might be cool if 23andMe had all that, but they don’t!

Instead, when you spit into a tube and send it to 23andMe, they run what’s called a DNA “chip” on your sample. This chip identifies less than a million individual nucleotides scattered around the genome (about 640,000, actually). But for the sake of argument, let’s say they have 1 million letters of your DNA. That’s a tiny percentage: about 0.02% of your genome. So no, they don’t have your genome, but they do have a small sample of it.

What’s fascinating–and a lot of fun, for some–is that by comparing these scattered landmarks, called SNPs or “snips,” you can get a very accurate picture of how closely related two people are. For example, you share half your DNA with your parents, siblings, and children, so you should share approximately half of these SNPs. For a niece or nephew, you share about 1/4 of your SNPs, and for a first cousin, 1/8. I have multiple relatives on 23andMe, and I can see them all in the DNA Relatives section. (I have fewer there now, because several of them deleted their data.)

23andMe also tells you your genetic “risk” for dozen of traits and a few genetic diseases. However–and here’s the rub–some 25 years after the human genome was sequenced, and despite huge efforts to link genes and disease, there are almost no SNPs that tell you anything consequential about your health. If you have a genetic disease, you almost certainly already know about it, and if you don’t know, then the 23andMe data just isn’t going to reveal anything.

Okay, so now that we’ve covered that, let’s go back to this privacy claim. The WashPost says you should worry because 23andMe might not protect your data, and might even sell it to a third party without your consent. My response is: so what?

The fact is that if you’re worried about privacy, you should be far, far more concerned about all the data that various companies are hoovering up about you based on your online activity. Are you browsing the web only in private or “in cognito” mode? If not, then companies are already buying and selling tons of information about you–information that is far more revealing than a SNP chip. Do you have a Facebook, Instagram, or TikTok account? Then you can be sure that Facebook and other companies know a great deal about you.

The privacy concern about DNA is that (according to some) it’s information that you can’t change. True enough–but plenty of other private information is just as permanent, or nearly so, and you’ve already shared that far more than you might realize.

But wait, some argue: genetic information might be used to deny health care coverage! I agree that this seems to be a serious concern, but first, note that this is only a problem because of our disastrous insurance-based, for-profit healthcare system in the U.S. If you live in Europe, where healthcare is provided to everyone by the government, then you don’t have this concern.

But even in the U.S., this fear is not a serious concern, because your SNP data reveals almost nothing useful about your health or your future risk of disease. So even the most ruthless, profit-driven insurance company isn’t going to find anything in your DNA data. Instead, they are much more likely to be interested in where you live, what you weight, what you eat, and other lifestyle choices that you’re making. And they can probably get that information simply by purchasing it from companies that are collecting it online, right now.

So no, I’m not deleting my DNA data from 23andMe, and you shouldn’t either. If you want to protect your privacy, there are much better ways to do that, such as browsing the web only in private mode, and getting rid of your social media accounts.

But when it comes to DNA, just chill out. No one can learn much about you from that.

Actually you have 22 pairs of chromosomes numbered 1 through 22, and if you’re a woman, you have a pair of X chromosomes, for a total of 23 pairs. If you’re a man, you have one X and one Y chromosome instead of two X’s, so the 23rd “pair” isn’t technically a pair at all, even though some parts of Y are identical to some parts of X.

Excellent post. As someone who has worked in cybersecurity (a cringe term we would never ourselves use) I would often get people asking me if “Siri was listening to me” because they had been talking with a friend, then later on started seeing ads on their iPhone relevant to that discussion despite never proactively searching for related terms.

At which point I’d have to explain that everything they did online was being bought and sold in auctions at millisecond latency. Everything their friends did too. Essentially the social graph of the entire planet and its online activities is traded as a commodity in real time.

In practical terms this means, yes, Google knows your friend came to your house. Google does not ask permission to track your location in the background for *your* benefit. They know what your friend has been searching, purchasing and discussing online.

They know you too, your demographics, your income, your relationship status. They know if you’re healthy, sick, sexually active, menstruating, depressed. They might not bundle your data with that level of specificity but they will slot you into a demographic.

Worrying about your DNA in the context feels a bit like worrying about catching a cold while you’re treading water in the ocean.

Hi Steven. First of all, I'm a long-time reader and admirer of your work. Thank you for sharing everything you do.

Your argument that "25 years after the human genome was sequenced...there are almost no SNPs that tell you anything consequential about your health" is shortsighted. Given the rapidity of scientific understanding, those SNPs could become far more predictive as machine learning and population genetics advance. Data collected now could be reanalyzed with future tools to reveal health risks, behavioral tendencies, or other sensitive information not apparent today.

Second, genetic data doesn't just reveal information about the individual—it exposes relatives who never consented to data collection. It can identify family members, reveal paternity, and expose genetic conditions in relatives. This creates privacy issues and, in some cases violations, extending beyond the original customer to their entire family tree, including future generations.

And then, of course, there's the thing we don't want to be thinking about, but are being forced to because of how the Trump administration is using data to locate immigrants in the U.S. Genetic databases are increasingly being used by law enforcement through techniques like genetic genealogy. While this can solve crimes, it also means genetic data can be accessed by authorities in ways 23andMe customers probably never anticipated when they spit into a tube.

Thanks for reading.

-Ed